When Rotation Hides in Plain Sight: Why Overhead (Transverse-Plane) Views Matter for Low Back Pain

By a physiotherapist who’s tired of seeing rotational problems missed from the front, and ‘magically’ manages to help clients get rid of back pain when rotation is under control.

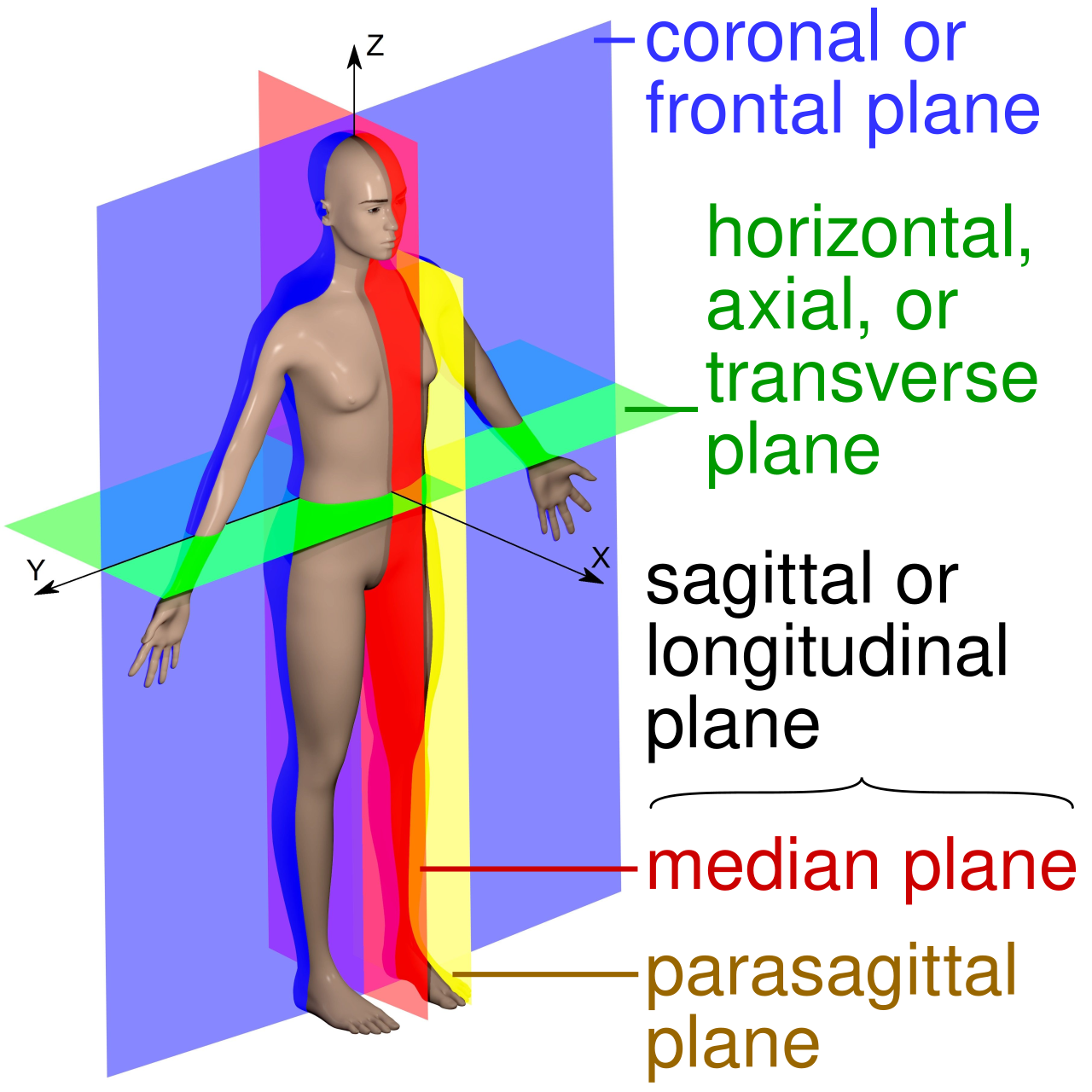

If you only ever look at posture and movement from the frontal plane, you will routinely miss the very thing that often aggravates the lumbar spine: rotation of the trunk and lumbopelvic girdle in the transverse (horizontal) plane. That blind spot has clinical consequences. A growing body of evidence shows people with low back pain (LBP) commonly display altered lumbopelvic coordination and rotation-related impairments - patterns you simply cannot trust a straight-on camera angle to reveal. [journals.plos.org], [frontiersin.org]

Below, I’ll summarize what the science says, why 3D motion capture with an overhead or freely rotatable 3D viewer changes the game, and how these insights connect to the specific 3D video examples you’ll see in this post.

In the video below is an athletic lady with recurrent lower back pain. She has had it on and off for years, despite being a young adult and leading the active lifestyle one might expect from a single person with a career and before starting a family. Despite numerous consultations with health and fitness professionals who claim to have assessed her posture and her movement in light of her signs and symptoms, no-one has been able to explain her specific needs, nor tell her specifically what to do about it.

They all looked at her from the front and the side, but NO ONE looked at her from above - so the information was not complete.

She has tried yoga and pilates, ‘back school’ exercises, and of course the usually non-specific ‘walk in the park each day’ - but the interventions were not personalised.

Here is the dilemma that 3D motion capture can fix for health professionals and their clients. When the overhead view or TRANSVERSE plane is missing in an assessment, then the assessment is incomplete ! So much happens in the hips, pelvis, lower back and trunk in the transverse plane !!

Proper INFORMATION is needed in order to make choices about the right INTERVENTION

So before geeking out on the evidence behind the relationship between rotation and lower back pain, have a look at how the overhead (transverse plane) view in this video highlights the amount of rotation occurring in the following foundational tasks (the stick figures only show the frontal view data). Keep in mind, this all happens quite fast, and with multiple body parts moving all at once - impossible for the human eye without the help of video playback and slow mo (even better with data in milliseconds and millimeters and degrees):

Standing posture - Note the lateral lean, and the uneven body weight distribution. Then note the amount of pelvic rotation from the overhead view! Hint number 1: the spine almost always combines lateral flexion with rotation.

Sidebend - It is very hard to move in the the frontal plane alone when there is rotation in the pelvis and/or the trunk. Her range of motion is excellent (which everyone has told her) despite the fact that the quality of movement is poorly controlled. Mobility without control is NOT a good combination. Hint number 2: imaging sidebending between 2 sheets of glass - do you touch the glass, or stay in plane, and at what point in the journey do you touch the glass? Start, middle, end, down-phase, up-phase, front or back and with the left or the right side?

Squat - When the pelvis is rotated, the hip joints are relocated, which in turn makes the legs behave asymmetrically. Hint number 3: when the feet are fixed on the floor, anything that happens in the pelvis will affect the legs. This is called a closed-chain system.

The evidence in a nutshell

Over one-third of individuals are afflicted with low back pain (LBP) every year , and recurrence rates have been cited as high as 44% within 1 year of onset. A major challenge in treatment of a patient suffering from LBP is the difficulty to determine a root cause using current diagnostic approaches. Most cases are categorized as non-specific LBP, with specific diagnoses only assigned in an estimated 10% of cases. LBP sufferers appear to demonstrate an altered lumbar and pelvic coordination and the alteration may persist even after symptoms have subsided:

smaller lumbar and larger pelvic contributions to trunk motion when compared to asymptomatic individuals

altered timing and coordination of pelvic and lumbar movements among patients with LBP.

(Ballard et al, 2020 citing others, Tanigichi et al, 2017).

When it comes to assessment, sometimes a movement might be because of a problem, and sometimes it might be causing the problem. Regardless, they go hand in hand and need to be identified and documented. How else will we know if a change in one affects the other. What is known is that people with LBP who regularly participate in leisure activities generally categorized as asymmetric displayed more trunk rotation-related impairments on examination than patients with LBP who regularly participated in leisure activities generally categorized as symmetric (Van Dillen et al 2006).It is important to repeat that movement asymmetry, rather than range of motion, may be a better indicator of disturbed function for people with LBP (El-Eisa et al 2006). The rhythm of the movement might be more important than the distance reached or the amount of stretch achieved. The latter seems to get so much attention in the health and fitness industries. This assessment bias could be motivated by the intervention bias: trainers can stretch you and surgeons can lengthen or fuse you.

Why 3D motion capture (and an overhead/horizontal-plane view) changes clinical decisions

You can actually see rotation and coupling. 3D capture quantifies pelvis/trunk angles in the transverse plane and reveals coupled motions (e.g., rotation + extension) that escalate facet loading and tissue stress. These patterns are documented both in 3D optical systems and advanced imaging/biomechanics studies.

You can verify asymmetry in closed‑chain tasks. When the feet are planted (squat), the pelvis/trunk’s rotational bias will often drive asymmetric knee paths that are obvious from overhead but nearly invisible from the front - helping you target the true driver rather than chasing knee “valgus” in isolation.

If you really want to geek out about the segmental contribution of the lumbar spine, then have a read of this deep lumbar kinematics study by McMullin et al, 2023.

Interpreting the 3D video (what to look for, and why it matters)The decision-making is up to the movement specialist after considering all the contextual factors that can contribute to movement dysfunction - signs, symptoms, past medical history, social, attitudes and beliefs… the list is long.

”How we move is both BEHAVIOURAL and MECHANICAL”

It is probably just a matter of time before BIOmechanics is accompanied by PSYCHOmechanics or even SOCIOmechanics, or maybe we will package them all together for BIOPSYCHOSOCIOmechanics. We did it with neuromusculoskeletal!

In any case, whatever we call it, the common feature here is that movement is a mechanical event, and it occurs in 3 planes of movement, with spatial and temporal components, involving a whole host of ‘degrees of freedom’. It is fair to say, too much going on for the human eye in real time, and much better left to an AI and 3D video to capture and analyse. The thinking, and the interpretation can be left to the human specialist in light of everything else.

From a purely mechanical perspective, the 3D video clip demonstrates the some of blind spots that a frontal view creates. Here’s how:

1) Standing posture

Observation: Pelvic rotation is evident from the overhead view; a weight shift bias is present.

Why overhead matters: From the front, you might only note a mild lateral shift. From above, you can see the hemipelvis oriented forward on the left, or backward on the right. This is consistent with rotation‑dominant postural asymmetry that relates to altered trunk mechanics in LBP populations.

Clinical tie‑in: LBP cohorts often display altered lumbopelvic rhythm/co-ordination and postural parameter differences (e.g., pelvic tilt) - warranting targeted movement retraining, not just static alignment cues.

2) Sidebend task

Observation: The sidebend is not pure frontal‑plane - there’s clear lumbopelvic rotation coupled into the movement.

Why overhead matters: 3D reveals the coupled rotation (frontal + transverse) that potentially increases segmental shear/extension-rotation stress - patterns associated with LBP phenotypes.

Clinical tie‑in: Excess spinal extension/flexion coupled with rotation is a recognized pattern in CLBP; encouraging neutral axial alignment while restoring segmental motion can reduce provocative loads. Assess for pain avoidance (antalgic movement), local and global strength deficits (concentric and eccentric), control deficits, co-ordination deficits.

3) Bilateral squat

Observation: The pelvis rotates during descent; the knees track asymmetrically - obvious overhead, subtle from the front. The closed‑chain nature couples one side to the other - the lumbopelvic girdle is driving the asymmetry.

Why overhead matters: From above, you can confirm that the pelvis is the driver, not simply a local knee issue. Squat biomechanics reviews emphasize that multi‑plane trunk/pelvis strategies influence lower‑limb path and joint loading. The research by Chris Powers comes to mind.

Clinical tie‑in: Address the rotational pelvis/trunk control first; otherwise you may over‑correct the knee and miss the upstream cause. 3D normative data for squats also highlight the stabilizing role of frontal/transverse planes despite sagittal dominance - another reason to measure rotation explicitly.

4) Single‑leg squat (SLS)

Observation: Appears less affected despite the rotated lumbopelvic girdle - consistent with the open‑chain nature minimizing obligatory coupling.

Why this makes sense: In SLS, the task constraints differ (one foot in contact, contralateral limb unloaded), so lumbopelvic rotation biases may be less expressed or present differently (often as trunk/pelvic strategy rather than knee path).

Clinical tie‑in: Don’t let a “clean” SLS fool you - although rotation‑dominant impairments are visibly the primary driver in bilateral closed‑chain tasks, the pelvic rotation can be disguised by internal rotation of the hip, often causing a dynamic valgus. The knee gets the blame, but in fact it is just helping disguise the pelvic rotation further up the kinematic chain.

Practical implications for assessment & rehab

Always get a transverse‑plane view. Add an overhead camera or use a 3D viewer to interrogate pelvis and trunk rotation during quiet stance, sidebend, bilateral squat, and SLS. 2D frontal alone is insufficient when accuracy matters.

Quantify lumbopelvic rhythm/coordination. Simple tasks can expose abnormal lumbo‑pelvic contributions in LBP; wearable IMUs and optical 3D systems are the gold standard (but expensive and clumsy), followed by markerless 3D systems, and can capture these reliably enough to guide progress, with caveats for transverse-plane variability.

Treat the driver, not the symptom. If overhead shows pelvic rotation driving knee asymmetry in squat, prioritize trunk/pelvic rotation control (motor control retraining, task-specific cues) before obsessing over tibiofemoral alignment. Evidence supports that targeted motor control programs can normalize lumbopelvic movement and improve outcomes. (Tsang et al, 2021)

Use task selection strategically. Expect rotational biases to manifest more in closed‑chain bilaterals; they may be less obvious in SLS. Build your progression/regression and cueing around what the 3D view actually shows. Sometimes it is about removing effort, rather than asking for more effort.

A note on technology

3D (marker‑based) motion capture remains the research gold standard for full‑body kinematics and coupling analysis. Newer work demonstrates segmental lumbar kinematics and coupling movement patterns (multidirectional) that simply cannot be inferred from single‑plane views.

Markerless 3D and IMU-based systems are increasingly practical. Meta-analyses report good - excellent agreement with gold standards for spatiotemporal measures and many sagittal/frontal angles, while advising caution for some transverse-plane metrics - precisely why a dedicated overhead/horizontal-plane perspective and multi-view verification are helpful.

Bottom line

Rotation lives in the transverse plane. If you don’t look from above - or better, use 3D motion capture with a 3D viewer - you will miss critical lumbopelvic and trunk behaviors associated with LBP. The overhead perspective in your video isn’t a gimmick; it’s the difference between seeing the driver and treating the by‑products.

by Glenn Bilby, Human Movement Scientist, Physiotherapist, MBA, Founder of Qinematic