Lower Back Hurt During Pregnancy - and Why It Sometimes Goes Away After?

Lower back pain and pelvic girdle pain are almost a rite of passage for many pregnant women -but the numbers might surprise you. Research shows 50–80% of women experience back pain during pregnancy, and pelvic girdle pain (PGP) affects more than half of expectant mothers, with 5–8% reporting severe pain and disability. The pain often peaks in the third trimester, thanks to hormonal changes (thankyou, Relaxin!), weight gain, and shifting posture (1). One in fifty working women who are on sick leave (in the Netherlands) due to pregnancy-related problems. In over 25% of young women receiving a disability pension, the situation was preceded by pregnancy and delivery. So the social costs are high, and easily justifies more investment in prevention for women before, during and after childbirth.

(4) Yoseph, E.T., et al (2025) Pregnancy-Related Spinal Biomechanics: A Review of Low Back Pain and Degenerative Spine Disease. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 858.

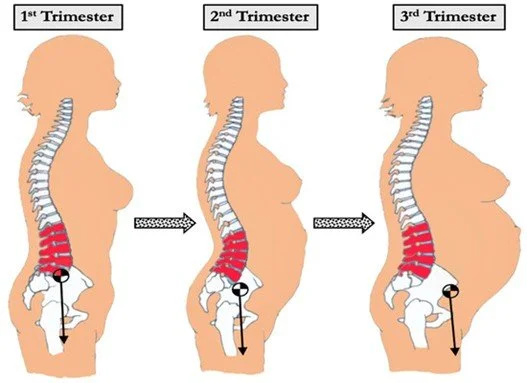

Changes during pregnancy

Physio-pedia.com propose the following features of postural changes that occur (6):

Anterior tilt of the pelvis.

Hyperextended knees.

Increased lumbar lordosis.

Posterior shift of gravity line.

Hyper kyphosis of the upper thoracic spine.

Protracted shoulders.

Anterior angulation of the cervical region.

Extension of the occiput on atlas.

Associated with these postural changes is a waddling gait pattern.

Postural changes as the fetus grows

But what about before and after pregnancy?

The majority of women recover spontaneously within three months after delivery, however a substantial number of women (30%) still report PGP after this period (2).

Why Does Back Pain Resolve After Some Pregnancies?

Interestingly, some women who had back pain before pregnancy report improvement afterward - possibly due to increased physical activity during pregnancy, targeted physiotherapy during and after pregnancy, improved core strength from structured postnatal rehab programs, and postural adjustments over time.

Before: Significant lower back pain during early pregnancy with postural dysfunction.

After: Less lower back pain and improvements in postre and movement quality 3 months after childbirth.

Several factors might contribute to back pain relief:

Hormonal Reset: After delivery, Relaxin and other hormones drop, allowing ligaments and joints to stabilize within 6–8 weeks. (3)

Postural Rebalancing: The spine returns to its pre-pregnancy alignment as the center of gravity shifts back.

Biomechanical Reviews: Pregnancy induces increased lumbar lordosis and anterior pelvic tilt to compensate for the forward shift in the center of gravity. After childbirth, these adaptations gradually reverse as body mass distribution returns to baseline and hormonal influences (like Relaxin) diminish. (4)

Postural Studies: Research using skeletal analysis systems found significant increases in lumbar curvature and pelvic tilt from the first to the third trimester, followed by reductions postpartum, indicating a trend toward pre-pregnancy alignment. (5)

Physiological Explanation: The postpartum period involves a “reset” of musculoskeletal mechanics - ligamentous laxity decreases, and the spine rebalances as the anterior load is removed. This is supported by clinical observations and biomechanical modelling.

Rehabilitation & Exercise: Many women engage in postnatal exercises, pelvic floor strengthening, and physiotherapy, which improve core stability and reduce pain.

Early, non-invasive monitoring of postural and movement changes, followed by preventive strategies such as targeted prenatal exercise are necessary (4).

Lifestyle Adjustments: Better posture awareness and gradual return to activity help prevent chronic pain.

Before Pregnancy

Physical Fitness: Women who are physically active before pregnancy have a lower risk of developing severe low back pain during pregnancy. Strong core and pelvic muscles provide better spinal support (7). Pre-exisiting injuries and imbalances that are likely to be aggravated by weight bearing and postural changes should be assessed and improved with prevention strategies.

Body Weight: Higher BMI before pregnancy is associated with increased risk of back pain during pregnancy and postpartum (7).

During Pregnancy

Exercise & Activity: Regular moderate physical activity (e.g., walking, swimming, prenatal yoga) reduces the incidence and severity of low back and pelvic girdle pain. Meta-analyses confirm exercise programs improve posture and muscle tone, reducing strain on the spine (8).

Posture Habits: Poor posture (e.g., prolonged sitting, slouching) and repetitive lifting increase mechanical stress on the lumbar spine. Education on ergonomics and posture correction during pregnancy helps prevent pain. Patient education should not stand alone, but should be combined with active treatment, such as exercise (9).

Lifestyle Choices: Smoking and sedentary behaviour worsen musculoskeletal health and increase pain risk. Conversely, maintaining healthy weight gain and staying active improve outcomes (7).

After Pregnancy

Postnatal Exercise: Targeted exercises (pelvic tilts, bridges, core strengthening) are effective in reducing postpartum back pain and restoring spinal stability. These exercises help reverse pregnancy-related postural changes and strengthen weakened muscles (10).

Daily Habits: Proper lifting techniques (bend knees, keep back straight), breastfeeding ergonomics (using pillows for support), and avoiding prolonged awkward positions reduce strain on the spine (11).

Sleep & Stress Management: Adequate rest and stress reduction improve recovery and reduce chronic pain risk.

Science Meets Technology: Motion Capture Studies

Motion capture studies - both marker-based and markerless - have provided detailed insights into how pregnancy alters posture, spinal curvature, and gait mechanics. These findings are crucial for designing ergonomic interventions and postnatal rehabilitation programs.

Biomechanics researchers have used motion capture systems to study spinal movement before, during, and after pregnancy. These systems track lumbar spine kinematics in 3D, revealing how pregnancy alters posture and range of motion. For example, optical marker-based studies show significant changes in lumbar lordosis and segmental velocities during functional tasks like walking and lifting. These market based systems are expensive, time consuming and inconvenient for use in a gym or clinic. Markerless systems like www.moovment.pro are becoming more common.

Examples of motion capture studies that have evaluated changes in posture and movement in pregnant women:

1. Balance and Gait Changes During Pregnancy

Catena et al. (2018–2023) conducted multiple studies using 3D motion capture and force plates to analyze gait and balance changes throughout pregnancy (12). Findings include:

Increased step width and decreased gait velocity as pregnancy progresses.

Altered joint kinematics (hip and trunk motion) to maintain stability.

These adaptations aim to reduce fall risk during pregnancy.

2. Systematic Review of Biomechanical Changes

Conder et al. (2019) reviewed 50 studies on pregnancy biomechanics, many of which used marker-based motion capture systems (e.g., Vicon) (13). Key observations:

Increased lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis.

Reduced trunk range of motion and hip extension.

Changes in center of pressure and stability indexes measured during gait tasks.

3. Stand-to-Sit and Functional Movements

Catena et al. (2019) used motion capture to study stand-to-sit kinematics during pregnancy. Results showed reduced sagittal plane hip motion and compensatory trunk adjustments to maintain balance (12).

4. Markerless Motion Capture Applications

Recent reviews highlight the growing use of markerless motion capture for pregnancy-related movement analysis, offering practical benefits for clinical settings. These systems can track posture and gait without reflective markers, making them suitable for real-world environments. Moovment Scan is currently being use at a lab in Czech republic for assessing the function and posture of pregnancy and post partum women.

by Glenn Bilby, Human Movement Scientist, Physiotherapist, MBA, Founder of Qinematic

References:

(1) Katonis P et al (2011) Pregnancy-related low back pain, HIPPOKRATIA 2011, 15, 3: 205-210

(2) Wiezer M, et al (2020) Risk factors for pelvic girdle pain postpartum and pregnancy related low back pain postpartum; a systematic review and meta-analysis, Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, Volume 48, August 2020

(3) Back Pain After Pregnancy, https://www.spine-health.com/conditions/pregnancy-and-back-pain/back-pain-after-pregnancy

(4) Yoseph, E.T., et al (2025) Pregnancy-Related Spinal Biomechanics: A Review of Low Back Pain and Degenerative Spine Disease. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 858.

(5) Franklin M (1998) An Analvsis of Posture and Back Pain in the First and Third Trimesters of Pregnancy, JOSPT, Vol 28, No 3, Sept 1998

(6) https://www.physio-pedia.com/The_Biomechanics_of_Pregnancy

(7) Health Tips for Pregnant Women - NIDDK

(8) https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/news/2024/moving-more-healthy-pregnancy

(9) Vesting S eta l (2025) Educating women to prevent and treat low back and pelvic girdle pain during and after pregnancy: a systematized narrative review, Annals of Medicine, 2025, VOL. 57, NO. 1

(10) https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/pdf/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

(11) Back pain during pregnancy: 7 tips for relief - Mayo Clinic

(12) https://labs.wsu.edu/biomechanics/pregnancy-balance-control/

(13) Conder, R.; Zamani, R.; Akrami, M. The Biomechanics of Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2019, 4, 72.